Raining Hydrocarbons in the Gulf – flashback

Below the Gulf of Mexico, hydrocarbons flow upward through an intricate network of conduits and reservoirs. They start in thin layers of source rock and, from there, buoyantly rise to the surface. On their way up, the hydrocarbons collect in little rivulets, and create temporary pockets like rain filling a pond. Eventually most escape to the ocean. And, this is all happening now, not millions and millions of years ago, says Larry Cathles, a chemical geologist at Cornell University. "We're dealing with this giant flow-through system where the hydrocarbons are generating now, moving through the overlying strata now, building the reservoirs now and spilling out into the ocean now," Cathles says.

"We're dealing with this giant flow-through system where the hydrocarbons are generating now, moving through the overlying strata now, building the reservoirs now and spilling out into the ocean now," Cathles says.

He's bringing this new view of an active hydrocarbon cycle to industry, hoping it will lead to larger oil and gas discoveries. By matching the chemical signatures of the oil and gas with geologic models for the structures below the seafloor, petroleum geologists could tap into reserves larger than the North Sea, says Cathles, who presented his findings at the meeting of the American Chemical Society in New Orleans on March 27.

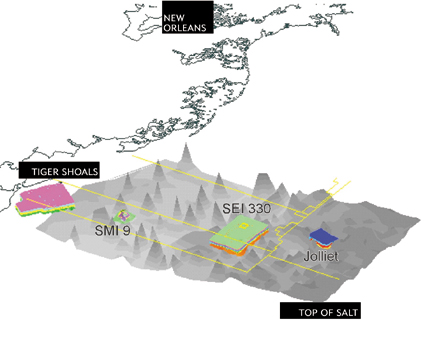

This canvas image of the study area shows the top of salt surface (salt domes are spikes) in the Gas Research Institute study area and four areas of detailed study (stratigraphic layers). The oil fields seen here are Tiger Shoals, South Marsh Island 9 (SMI 9), the South Eugene Island Block 330 area (SEI 330), and Green Canyon 184 area (Jolliet reservoirs). In this area, 125 kilometers by 200 kilometers, Larry Cathles of Cornell University and his team estimate hydrocarbon reserves larger than those of the North Sea. Image by Larry Cathles.

Cathles and his team estimate that in a study area of about 9,600 square miles off the coast of Louisiana, source rocks a dozen kilometers down have generated as much as 184 billion tons of oil and gas — about 1,000 billion barrels of oil and gas equivalent. "That's 30 percent more than we humans have consumed over the entire petroleum era," Cathles says. "And that's just this one little postage stamp area; if this is going on worldwide, then there's a lot of hydrocarbons venting out."

According to a 2000 assessment from the Minerals Management Service (MMS), the mean undiscovered, conventionally recoverable resources in the Gulf of Mexico offshore continental shelf are 71 billion barrels of oil equivalent. But, says Richie Baud of MMS, not all those resources are economically recoverable and they cannot be directly compared to Cathles' numbers, because "our assessment only includes those hydrocarbon resources that are conventionally recoverable whereas their study includes unconventionally recoverable resources." Future MMS assessments, Baud says, may include unconventionally recoverable resources, such as gas hydrates.

Of that huge resource of naturally generated hydrocarbons, Cathles says, more than 70 percent have made their way upward through the vast network of streams and ponds, venting into the ocean, at a rate of about 0.1 ton per year. The escaped hydrocarbons then become food for bacteria, helping to fuel the oceanic food web. Another 10 percent of the Gulf's total hydrocarbons are hidden in the subsurface, representing about 60 billion barrels of oil and 374 trillion cubic feet of gas that could be extracted. The remaining hydrocarbons, about 20 percent, stay trapped in the source strata.

Driving the venting process is the replacement of deep, carbonate-sourced Jurassic hydrocarbons by shale-sourced, Eocene hydrocarbons. Determining the ratio between the younger and older hydrocarbons, based on their chemical signatures, is key to understanding the migration paths of the oil and gas and the potential volume waiting to be tapped. "If the Eocene source matures and its chemical signature is going to be seen near the surface, it's got to displace all that earlier generated hydrocarbon — that's the secret of getting a handle on this number," Cathles says.

Another important key to understanding hydrocarbon migration is "gas washing," Cathles adds. A relatively new process his research team discovered in the Gulf work, gas washing refers to the regular interaction of oil with large amounts of natural gas. In the northern area of Cathles' study area, he estimates that gas carries off 90 percent of the oil.

Ed Colling, senior staff geologist at ChevronTexaco, says that identifying the depth at which gas washing occurs could be extremely useful in locating deeper oil reserves. "If you make a discovery, by back tracking the chemistry and seeing where the gas washing occurred, you have the opportunity to find deeper oil," he says.

Using such information in combination with the active hydrocarbon flow model Cathles' team produced and already existing 3-D seismic analyses could substantially improve accuracy in drilling for oil and gas, Colling says. ChevronTexaco, which funds Cathles' work through the Global Basins Research Network, has been working to integrate the technologies. (Additional funding comes from the Gas Research Institute.)

"All the players are looking for bigger reserves than what's on shore," Colling says. And deep water changes the business plan. With each well a multibillion dollar investment, the discovery must amount to at least several hundred million barrels of oil and gas for the drilling to be economic. Chemical signatures and detailed basin models are just more tools to help them decide where to drill, he says.

"A big part of the future of exploration is being able to effectively use chemical information," Cathles says. Working in an area with more oil by at least a factor of two than the North Sea, he says he hopes that his models will help companies better allocate their resources. But equally important, Cathles says, is that his work is shifting the way people think about natural hydrocarbon vent systems — from the past to the present.

Lisa M. Pinsker

"Destroying the New World Order"

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING THE SITE!

Latest Activity

- Top News

- ·

- Everything

Ghislaine Maxwell & The Secret "Shadow" 9/11 Commission? | John Kiriakou

When the Communists Take Over America!...Famous 1957 Anti-Communist Movie

When the Communists Take Over America!...Famous 1957 Anti-Communist Movie

Are the End Times Drawing Near?

Catherine Fitts: Epstein, CIA Black Budget, the Control Grid, and the Banks’ Role in War

Ключові слова в тексті: як органічно їх вписати в статтю

© 2026 Created by truth.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of 12160 Social Network to add comments!

Join 12160 Social Network