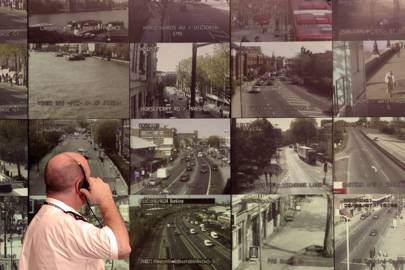

The UK's mass surveillance regime has broken the law (again)

The UK's mass surveillance regime has broken the law (again)

The UK has a long history of surveillance – and it continues to be unlawful. In the latest damning judgement of British security operations the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has ruled the government unlawfully obtained data from communications companies and didn't put in place safeguards around how it did it.

In its judgement, the court said the UK's bulk interception regime violated the right to privacy as there wasn't enough oversight for how data was collected. It also ruled that how data was collected from tech companies broke human rights laws.

The challenge, which was brought to the ECHR by a number of human rights and journalism organisations including Amnesty International, Privacy International and Liberty, follows revelations by Edward Snowden in 2013 that the UK government was using a number of mass surveillance programs within the Government Communications’ Headquarters (GCHQ) to intercept and store data about private communications.

However, in its decision the ECHR did not say that the UK having a bulk data collection scheme broke the law. The fact it didn't properly govern how data was collected led to it being unlawful in this case and only applies to previous laws.

In June 2015, the investigatory powers tribunal – the independent body reviewing whether the law is violated in particular cases of state surveillance – ruled that UK intelligence had unlawfully intercepted communications of Amnesty International and South Africa’s Legal Resources Centre. Corey Stoughton, advocacy director at Liberty, explains that the ECHR’s ruling is likely to put the spotlight on government’s shortcomings on privacy protection. “The question at the heart of this case was the broader one of whether the mass surveillance regimes that, at the time, allowed for the shocking spying on those two organisations is unlawful,” she says. “The ECHR, in the hierarchy of courts, was as high as we could take the case – so we are hoping that the ruling will have a lot of ramifications.”

The case is the latest in a slew of defeats that the UK government has suffered around its previous surveillance laws. The story is often the same: leaks expose government surveillance practices, these are challenged in court and, in many cases, the UK government loses. “Secrecy has always been put on a higher footing than legality in the history of the British state,” says Bernard Keenan, a lecturer in law at Birkbeck, University of London.

Since the Snowden revelations, however, things have changed. Until then, state surveillance was largely conducted under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (Ripa), created in 2000. There were some provisions under the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Act 2014 (Dripa). There's little mention or oversight of the powers which turned out to be used by the government inside GCHQ for surveillance programs such as Tempora, Prism or Upstream. Powers which led to bulk interception and storage of private communication content and datasets – in other words, what your messages contain, who you are sending them to, from where, at what time and so on.

Powers that worked behind the scenes and were revealed in 2013. In the face of public outcry, Theresa May, Home Secretary at the time, introduced in 2015 a brand-new mass surveillance law; the Investigatory Powers Act, which was passed in 2016. The law – dubbed the Snooper's Charter by critics – added some privacy safeguards but made many intrusive spy powers legal for the first time. In the latest case, the ECHR refused to rule on whether the UK's new bulk surveillance powers were lawful, as they were being replaced by the Investigatory Powers Act.

“Everything that was revealed by Snowden,” says Keenan, “GCHQ, Tempora, Upstream… None of those capacities have diminished. What’s happened is that the law now makes transparent a large amount of what the authorities were doing anyway. But the mass surveillance regime has not changed – at the best, you can say that the oversight regime has been enhanced.”

The fact that the government is trying to put legal foundations under a mass surveillance regime that already exists is something, Stoughton hopes, that will be brought to public attention after the ECHR ruling: “The debate that will be ongoing next is: are those legal foundations a violation to our right to privacy?”

As early as 1984 antiques dealer James Malone was charged with handling stolen property – but during his prosecution, a police officer accidentally read the transcript for a call intercepted from a tapped phone. The case was taken to the ECHR, which ruled that the interception interfered with the right to private life, and led to Parliament passing the Interception of Communications Act in 1985.

More recently, Liberty gathered more than 200,000 signatures for a petition to repeal the new surveillance laws implemented by the Investigatory Powers Act in 2016. It crowdfunded £40,000 in January 2017 to finance a legal challenge against the government, targeting its power to store and access citizens’ communication data from private companies, such as internet histories, emails or text and phone records, regardless of suspicion of criminal activity.

In April, the UK’s high court ruled that this part of the Investigatory Powers Act went against human rights as it granted ministers to order data retention arbitrarily and without prior authorisation. The government has until November 1 this year to change the law.

In December 2016 the EU's highest court ruled the UK keeping emails and electronic communications under its expired Dripa law was "general an indiscriminate". Previously, ]in 2015, Dripa was ruled unlawful by the UK's High Court. In January this year the UK Court of Appeal agreed with these rulings in another blow to surveillance laws.

This followed a 2016 decision from the Investigatory Powers Tribunal that said GCHQ, MI5 and MI6 had been collecting bulk data in a way that wasn't compatible with human rights.

Paul Bernal, a researcher on the interaction between human rights and internet privacy from the London School of Economics, says: “The Investigatory Powers Act needs to be changed, because what can be assumed now is that generally all our communications data can be gathered and stored. There should at least be a clause by which authorities would have to prove that the information they hold is valuable, and if not, they would have to get rid of it.”

This would be a way to regulate what, until now, has consisted of sweeping up in bulk private communications content and data, and allow for a targeted surveillance regime in which interception of communication would require a specific reason.

Bernal, however, sees a looming change that is likely to force the government to radically revise its data protection laws: with the UK imminently leaving the European Union, it will become necessary to adjust the surveillance regime. A prerequisite to exchanging data with the EU, in effect, is to prove that it is gathered in accordance to what the EU considers adequate protection of individuals. And by “adequate”, the EU means a regime in which secret activities relating to privacy are foreseeable by citizens.

“As members of the European Union, we don’t have to prove adequacy,” says Bernal. “The default position is that our regime is adequate, and you have to prove your case in court if you think it isn’t. Once we leave, it will be the other way round – our default position will be inadequate, and we will have to prove that it is.”

Bernal predicts that this will be difficult because the current laws are too intrusive. But exchanging data with the EU is crucial from many points of view – so the law will hopefully change to improve the protection of citizens’ rights. Something to look forward to in what some may call the not-so-merry prospect of Brexit.

Comment

-

Comment by DTOM on September 14, 2018 at 7:33pm

-

It's fight or die.

...And there is no-where left to run to.

-

Comment by cheeki kea on September 14, 2018 at 4:49am

-

Fight or Flight are the two best choices, for the rest of us. (If one goes wrong, the others for back up) I hope you all have your contingency plans in place. Things are getting nasty.

-

Comment by Chris of the family Masters on September 14, 2018 at 4:10am

-

Well, we have two choices. Either we learn ( en masse ) how to lawfully deal with the pirates, or there are fully manned FEMA camps awaiting sheeple arrival.

Sorry for being so forward.

-

Comment by DTOM on September 13, 2018 at 7:44pm

-

I agree, but try to convince the average Brit of that...

It's going to take an enormous upheaval before they even begin to comprehend the true paradigm...there is simply no other way.

-

Comment by Chris of the family Masters on September 13, 2018 at 7:27pm

-

Every single act, bill, citation, by-law past Imperial, is simply null and void.

"Destroying the New World Order"

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING THE SITE!

Latest Activity

- Top News

- ·

- Everything

Orwell - Football, Beer & Gambling

I, Pet Goat VI by - Seymour Studios | I, Pet Goat 6

Official Trailer NOVA '78 directed by Aaron Brookner and Rodrigo Areias

Peter Sellers - The Party (opening scene)

Disgraced Former CNN Anchor Don Lemon Arrested

© 2026 Created by truth.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of 12160 Social Network to add comments!

Join 12160 Social Network