UK police are lobbying the government to be given access to every UK Internet user's Web browsing history as part of the new Snooper's Charter—the Investigatory Powers Bill—which is expected to be published next week. According to The Guardian, the police want to revive the controversial plan for ISPs to store details about every website visited by customers for 12 months, an idea first mooted in the original Communications Data Bill, which was dropped after opposition from the Liberal Democrats when they were part of the previous coalition government.

Richard Berry, the National Police Chiefs’ Council spokesman for data communications, is quoted as saying: "We essentially need the ‘who, where, when and what’ of any communication"—who initiated it, where were they and when did it happened. And a little bit of the ‘what’, were they on Facebook, or a banking site, or an illegal child-abuse image-sharing website?"

Further Reading

According to The Guardian, Berry accepted that it was "far too intrusive" for police to be able to access the content of online searches and social media messaging without additional controls—for example, by requiring a warrant signed by a judge.

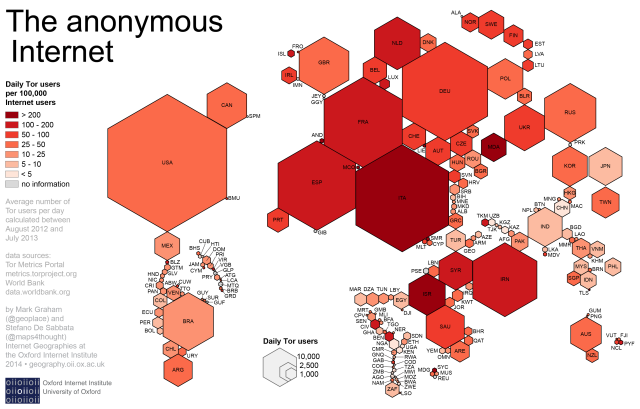

One of the problems with the idea of allowing police access to somebody's Web browsing history for the previous year is that, taken in aggregate, that information gives a very detailed picture of a person's life, and is thus just as intrusive as viewing online searches or social media messages. Another issue is that it is easy to circumvent this kind of snooping by using Tor or a VPN, both of which would obfuscate your behaviour enough that your ISP can't track you.

The move by the police seems to be part of a larger campaign by the UK's security apparatus to push for the long-expected Investigatory Powers Bill to grant them as many new powers as possible. As Ars reported yesterday, both GCHQ and MI5 have been making the case for increased online surveillance, which they like to frame as "merely" retaining capabilities they enjoyed when communications were analogue. Although it is true that the fraction of messages that they can track has gone down in recent years, this overlooks the fact that the overall volume of communications has gone up even more substantially, which outweighs any percentage loss.

Glyn Moody / Glyn Moody is Contributing Policy Editor at Ars Technica. He has been writing about the Internet, free software, copyright, patents and digital rights for over 20 years.

@glynmoody on Twitter

You need to be a member of 12160 Social Network to add comments!

Join 12160 Social Network